It's taken me forever to write this one, and when I wrote 80% of it last year, there were way way less resources available on how vLLM works under the hood, now a quick search on youtube shows dozens of new in depth videos. Still, I wanted to write down my understanding of the system as I learned it, and I hope it helps others get up to speed. I focused more on the core abstractions that I tend to work with, what they're doing and how they're related.

For those of you who don't use it, I would highly recommend using deepwiki when you're working on vLLM beyond just instantiating an OpenAI compatible server. It's an amazing resource to help you understand all the settings, features and flags that are available once you start to try and tweak the system for your usecase and model.

All of my illustrations here are just screengrabs from a great presentation the creators of vLLM did at the Ray Summit in 2023 which I highly recommend watching if you want to go deeper.

While there have been many releases since then, the core concepts remain the same.

A 50-line server to set the stage

Hosting your own LLMs has never been easier. In about 50 lines of code you can set up a remote LLM server powered by Modal and vLLM. This is not a production setup, but it makes it absurdly easy to experiment.

# credit to https://github.com/dwarvesf/llm-hosting

import os

import subprocess

import secrets

from modal import Image, Secret, App, enter, gpu, method, web_server

MODEL_DIR = "/model"

BASE_MODEL = "meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-8B-Instruct"

### Define a container image

def download_model_to_folder():

from huggingface_hub import snapshot_download

from transformers.utils import move_cache

os.makedirs(MODEL_DIR, exist_ok=True)

snapshot_download(

BASE_MODEL,

local_dir=MODEL_DIR,

ignore_patterns=["*.pt", "*.bin"], # Using safetensors

)

move_cache()

### Image definition

image = (

Image.from_registry("nvidia/cuda:12.1.1-devel-ubuntu22.04", add_python="3.10")

.pip_install(

"vllm==0.6.1.post2",

"wheel==0.44.0",

"packaging==24.1",

"huggingface_hub==0.25.0",

"hf-transfer==0.1.8",

"torch==2.4.0",

)

.apt_install("git")

.run_commands(

"pip install flash-attn==2.6.3 --no-build-isolation",

)

# Use the barebones hf-transfer package for maximum download speeds. No progress bar, but expect 700MB/s.

.env({"HF_HUB_ENABLE_HF_TRANSFER": "1"})

.run_function(

download_model_to_folder,

secrets=[Secret.from_name("huggingface")],

timeout=60 * 20,

)

)

app = App("vllm-llama3-8b", image=image)

GPU_CONFIG = gpu.A100(size="40GB", count=1)

# Run a web server on port 7997 and expose the OpenAI compatible Server

@app.function(

allow_concurrent_inputs=100,

container_idle_timeout=15,

gpu=GPU_CONFIG,

secrets=[

Secret.from_name("huggingface"),

Secret.from_dotenv(),

],

)

@web_server(8000, startup_timeout=300)

def openai_compatible_server():

target = BASE_MODEL

cmd = f"python -m vllm.entrypoints.openai.api_server --model {target} --port 8000"

subprocess.Popen(cmd, shell=True)

Modal makes it trivial to spin up GPUs and attach them to a vLLM engine using an SDK that mirrors OpenAI's. This powerful one liner does all the heavy lifting, and it is exactly what I want to unravel in this blog series.

The integration is intentionally friendly, but once you hit production workloads, it helps to understand how the engine actually behaves.

LLMEngine in one picture

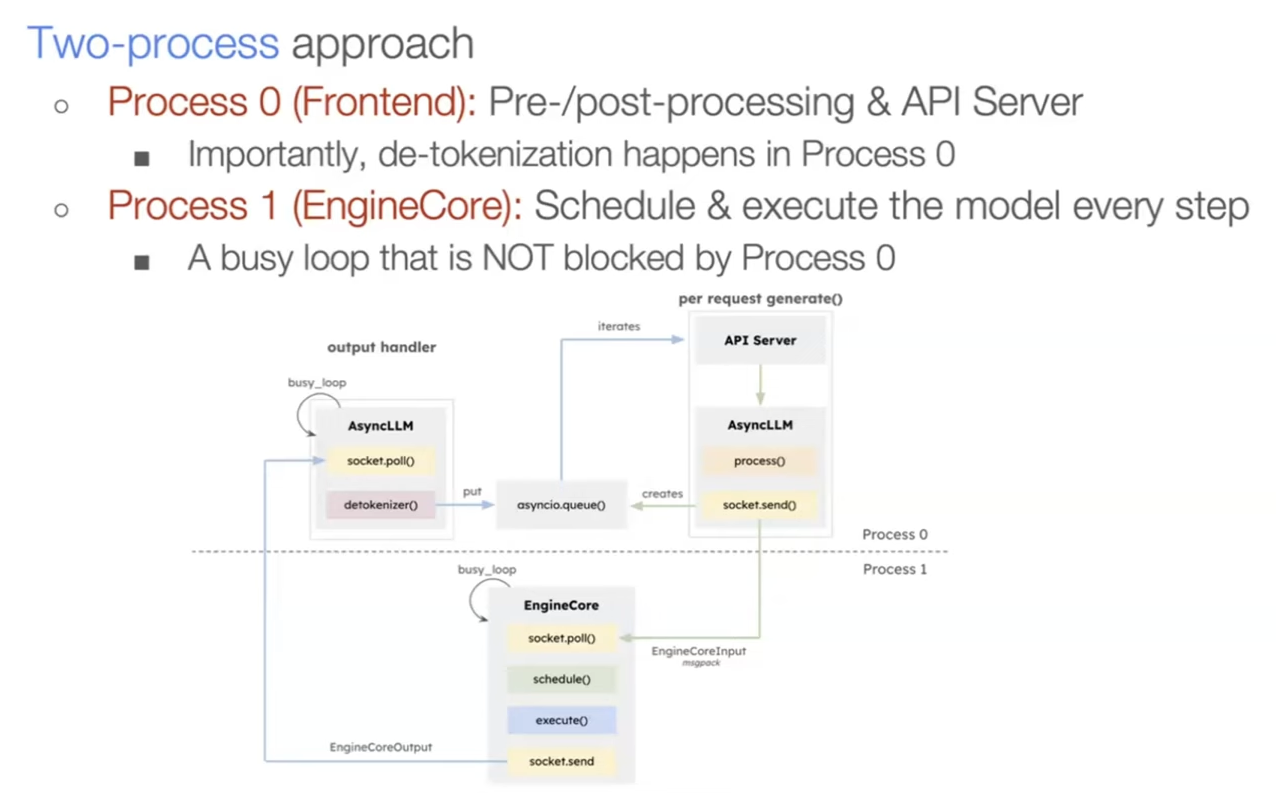

At the heart of vLLM is the LLMEngine, a class that encapsulates the model and manages the end-to-end lifecycle of inference requests. Conceptually, LLMEngine is responsible for:

- Input processing: tokenizing incoming prompts into model-readable token IDs.

- Scheduling: deciding which requests to process next and grouping them for efficient batch execution.

- Model execution: running forward passes on the model, sometimes across multiple GPUs.

- Output processing: decoding tokens back into text and formatting results.

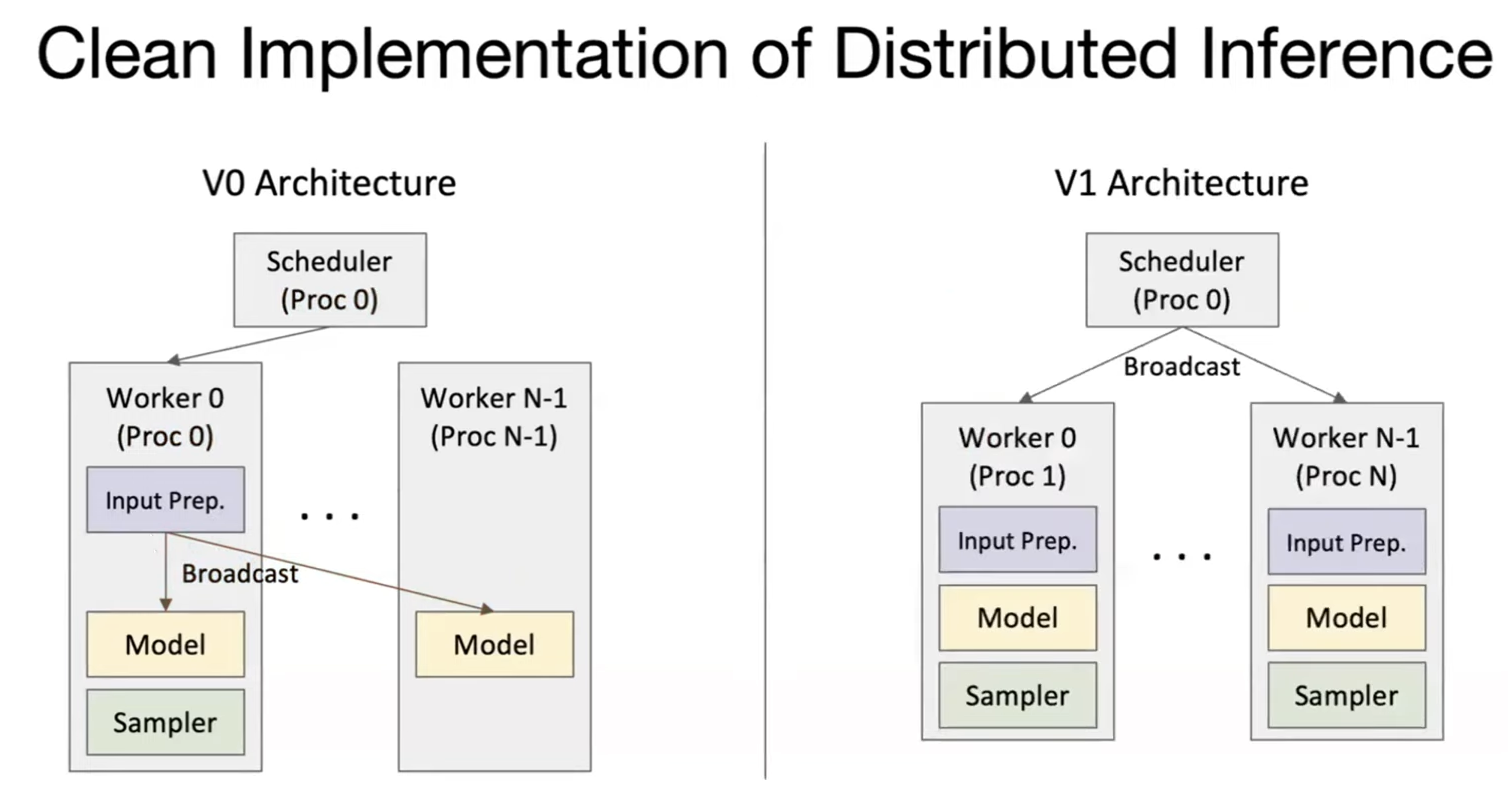

At the system level, vLLM keeps the scheduler and workers cleanly separated; the v1 architecture makes that boundary explicit.

The engine loop is tight and repetitive: take requests, tokenize, schedule, run the model, decode, and stream back.

Memory management is the scaling lever

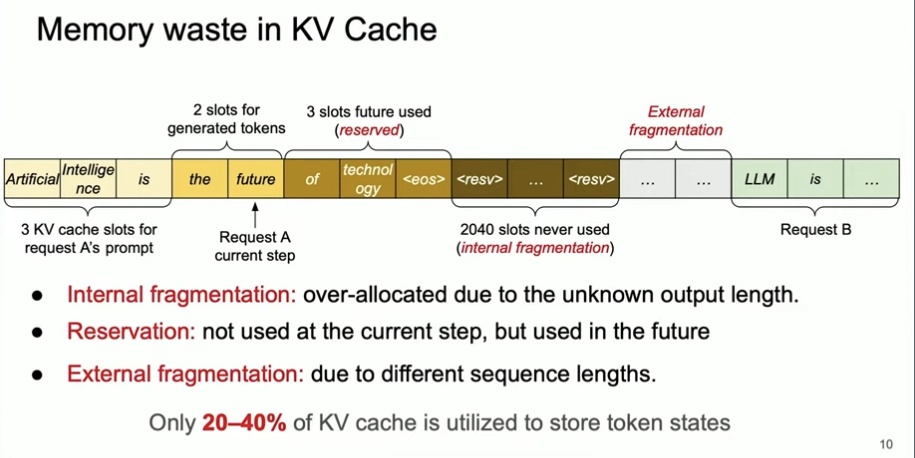

Once you move from a single prompt to many concurrent prompts, memory becomes the limiting factor. GPU compute scales, but the KV cache grows with sequence length and batch size. A naive cache strategy is to allocate a contiguous KV buffer per request sized for the prompt plus max_tokens. It is safe, but it is also incredibly wasteful.

The waste shows up in a few predictable ways:

- Internal fragmentation: you reserve space for the max output length even though most requests end early.

- Reservation waste: decode steps hold slots for future tokens that are not real yet.

- External fragmentation: different sequence lengths leave holes between allocations.

The result is low KV cache utilization and an artificial cap on concurrency. Fixing memory packing is the unlock, which is why vLLM's core innovation is about paging, not just batching.

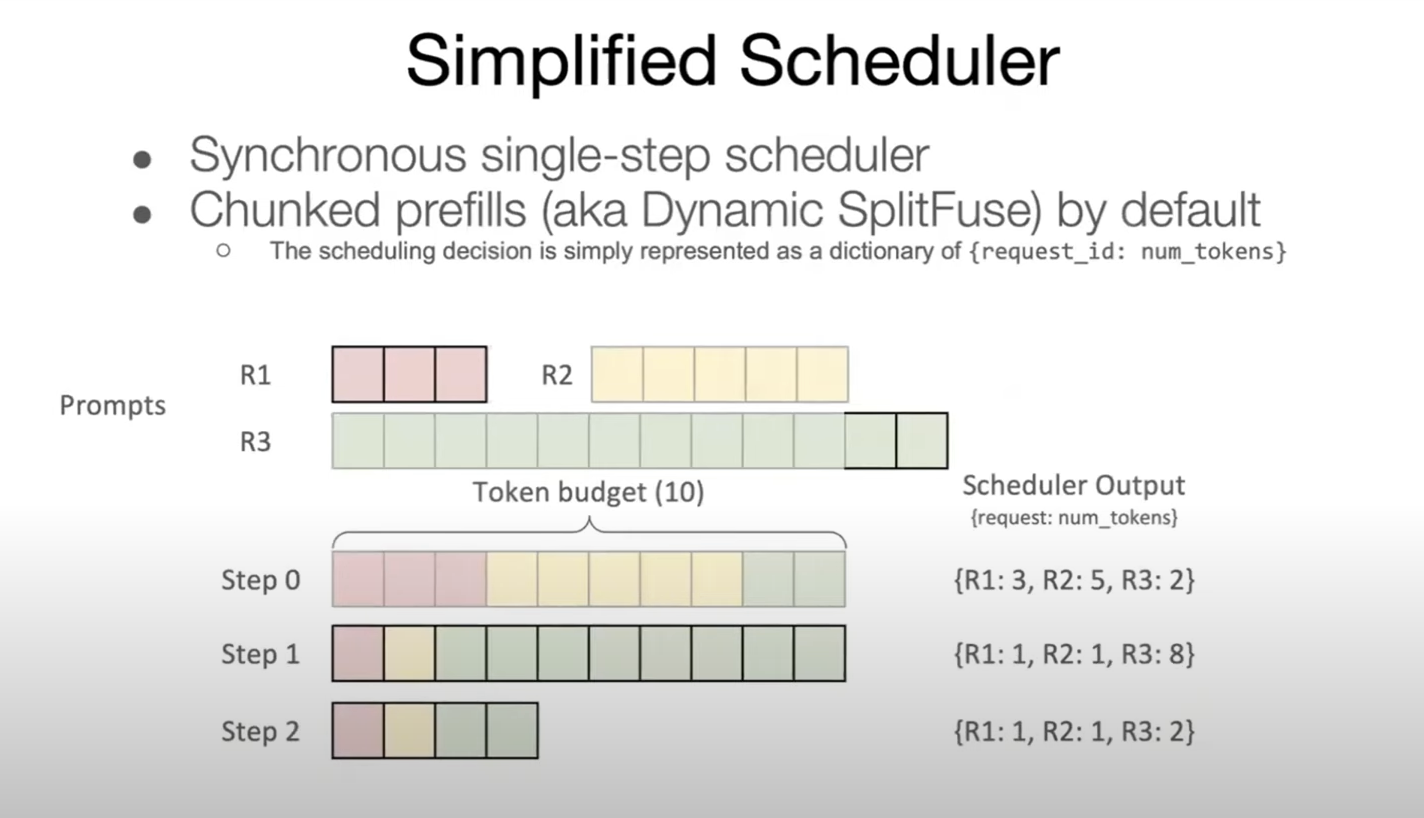

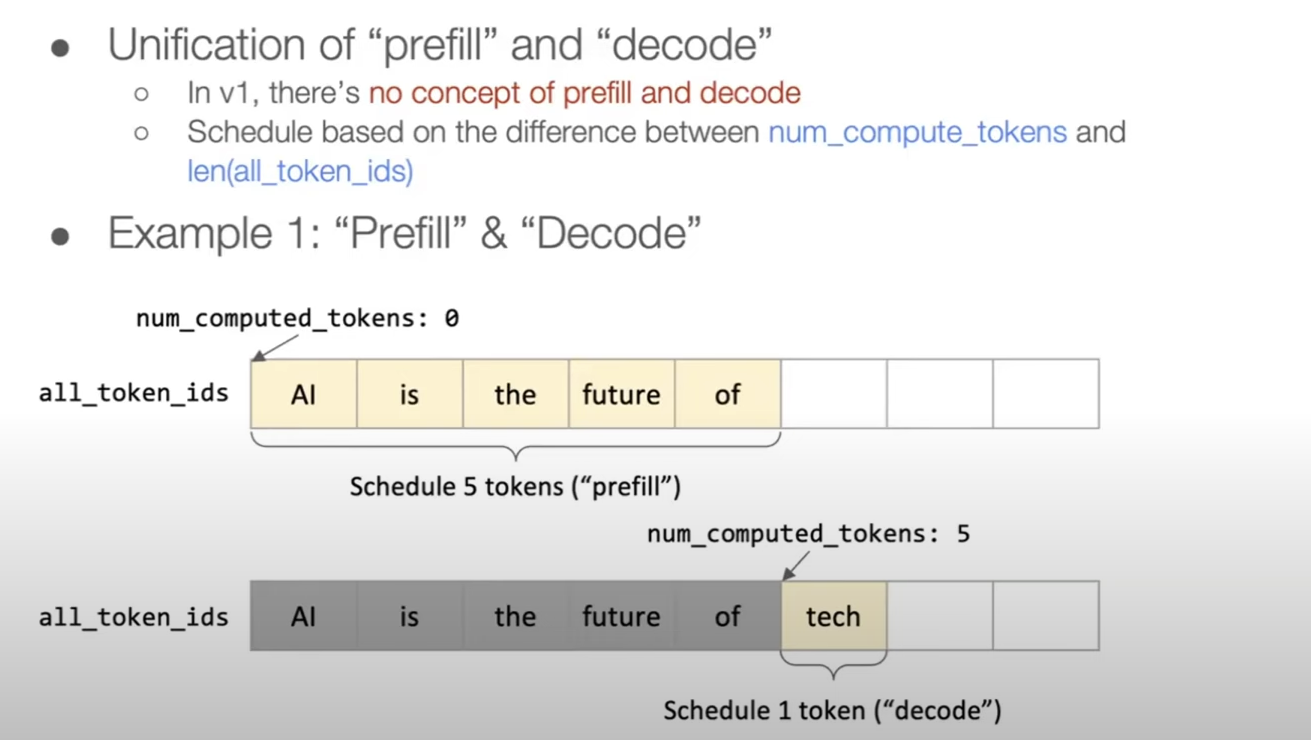

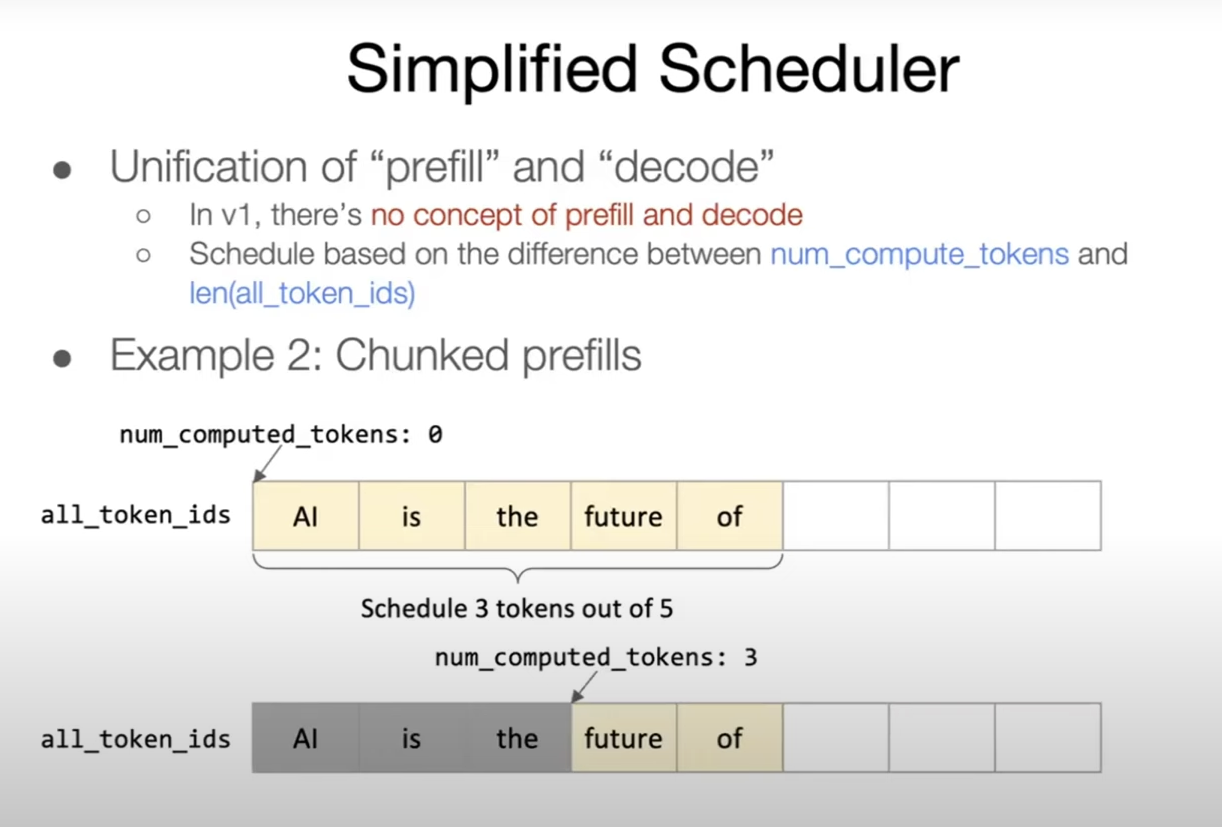

The scheduler: prefill vs decode

vLLM treats prefill and decode differently for good reason.

- Prefill is the first forward pass over the prompt. It is compute heavy and creates the initial KV cache.

- Decode is the token-by-token generation phase. It is latency sensitive and heavily constrained by KV cache reads.

vLLM tries to balance both in a single iteration. It uses a token budget so the batch stays within memory limits, then fills that budget with a mix of prefill chunks and decode tokens. That is why you will see references to max_num_batched_tokens and tracking how many tokens have already been computed for each request.

The basic idea is simple: keep the GPU busy while protecting latency. Prefill can be chunked and scheduled opportunistically, while decode gets priority to keep streams responsive.

PagedAttention and the KV cache

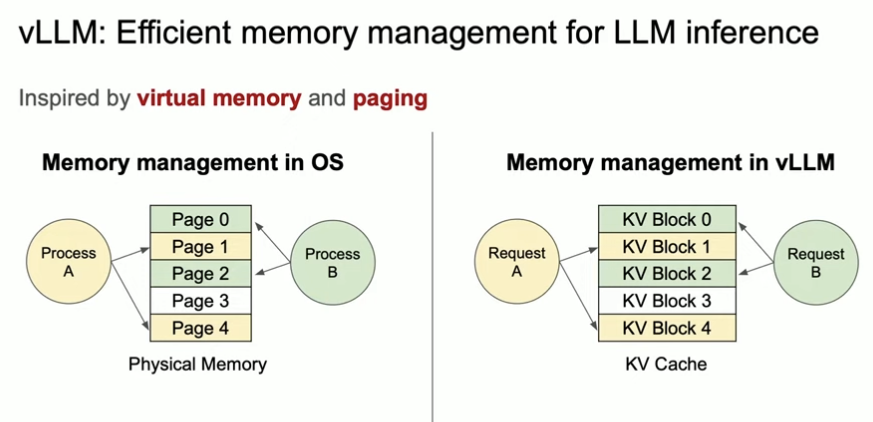

The KV cache is the real bottleneck. If you can keep it dense and avoid fragmentation, you can serve more concurrent requests.

vLLM borrows the idea of memory paging from operating systems. Instead of allocating one giant, contiguous KV cache per request, it allocates fixed-size blocks (pages) and maps each sequence to a list of blocks. Blocks are usually 16 tokens (sometimes 32 depending on kernels), which reduces fragmentation and keeps allocations simple.

This is what people mean by space multiplexing in vLLM: many requests share the GPU memory pool at the same time, each owning a scattered list of pages rather than a single contiguous slab.

Key effects:

- Lower fragmentation: fixed blocks prevent wasted tail space.

- Faster scheduling: the block table lets vLLM quickly assemble a batch.

- Better concurrency: more sequences fit in the same memory footprint.

Eviction, swapping, and recompute

When GPU memory gets tight, vLLM can evict KV cache content. There are two granularities to think about:

- Request-level eviction: drop a whole sequence when it is inactive or long-lived.

- Page-level eviction: evict the cold blocks of a sequence and keep the hot prefix.

Once evicted, vLLM has two options:

- Swap to CPU and reload later. This saves compute but adds PCIe latency.

- Recompute the KV cache from the prompt when needed. This saves memory bandwidth but burns compute.

Which path is best depends on your workload. Long prompts with occasional reuse benefit from swapping. Short prompts with high throughput often tolerate recompute.

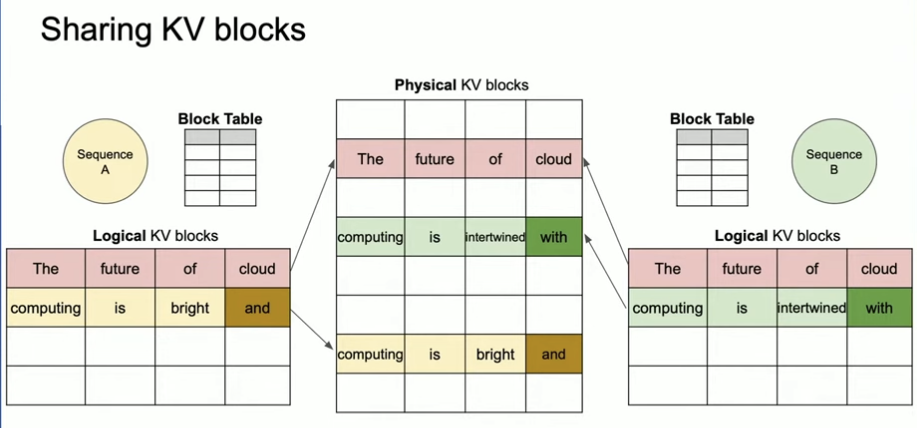

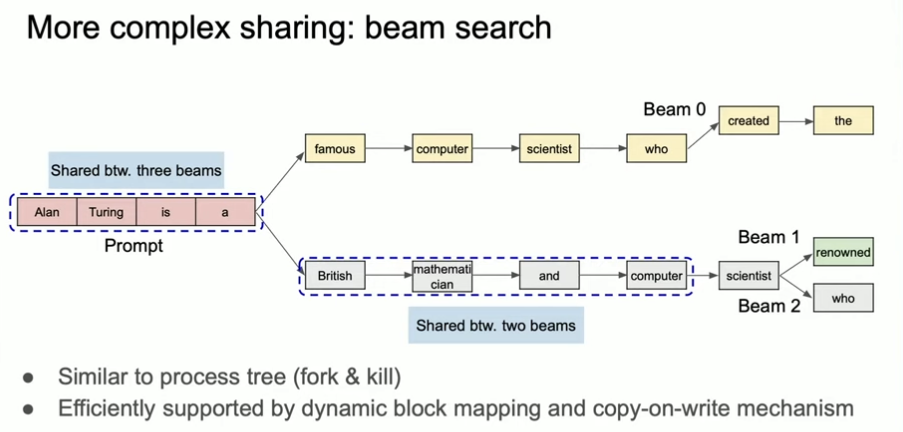

Parallel sampling without paying the full price

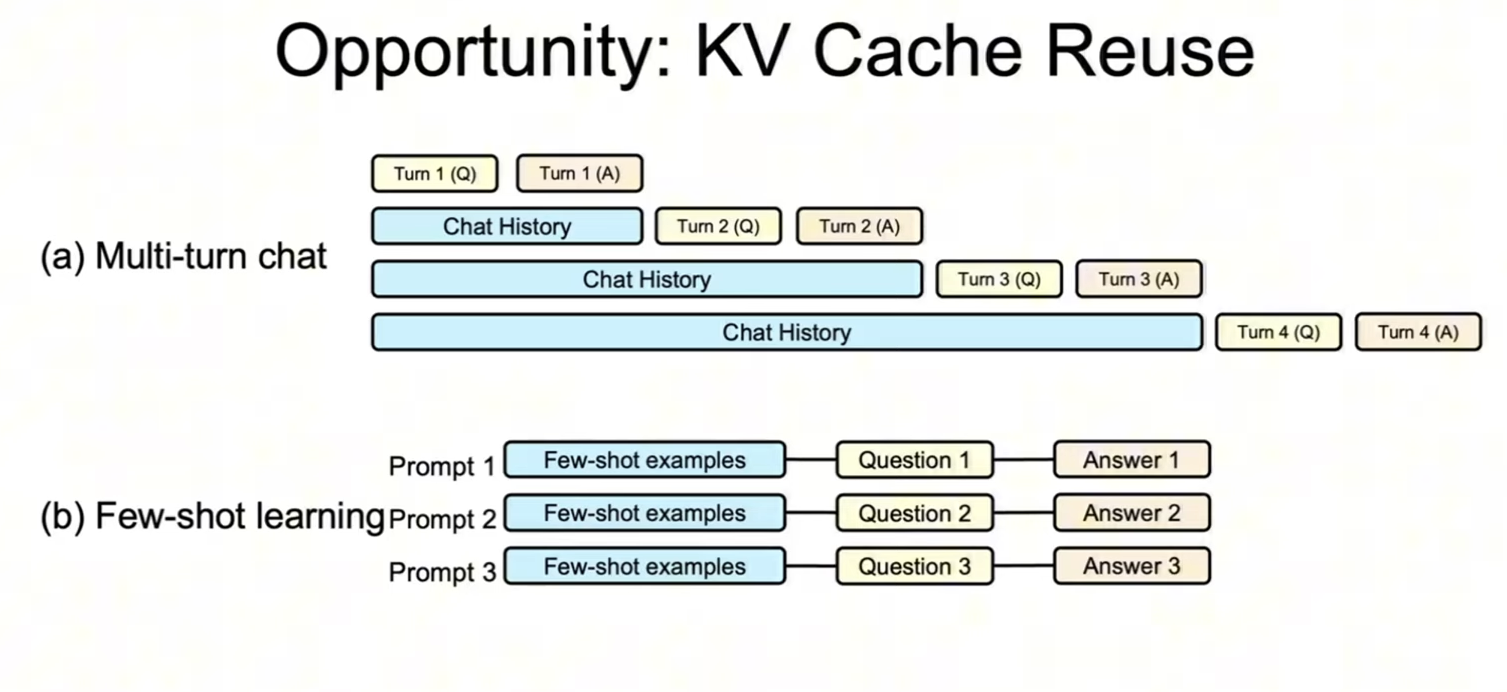

Parallel sampling (for example n > 1 or beam search) is a perfect fit for paged KV cache. All samples share the same prompt prefix, so the KV blocks for that prefix are shared. Only the divergent tokens allocate fresh blocks, which means you do not pay full KV cost per sample.

This is one of the quieter wins in vLLM. Parallel sampling feels expensive on paper, but with paged KV cache, the marginal cost per sample is much smaller than you would expect.

That same prefix reuse shows up in multi-turn chat and few-shot prompts, which is why cached prefixes are so valuable.

Radix trees and RadixAttention (SGLang)

A radix tree stores common prefixes in shared nodes. In LLM land, that makes it a natural structure for KV reuse across many prompts that start the same way.

SGLang's RadixAttention uses a radix tree to cache KV blocks. The tree is maintained with an LRU policy so rarely used branches get evicted first, while popular prefixes stay hot. You can think of it as the same paging idea but optimized for prefix sharing across many requests.

Scheduler evolution: v1 to today

The scheduler has evolved as vLLM moved from a simple "batch until full" approach to a more nuanced token-based budget.

In the early v1 scheduler, the primary controls were things like max_num_seqs and max_num_batched_tokens. It worked, but it was blunt.

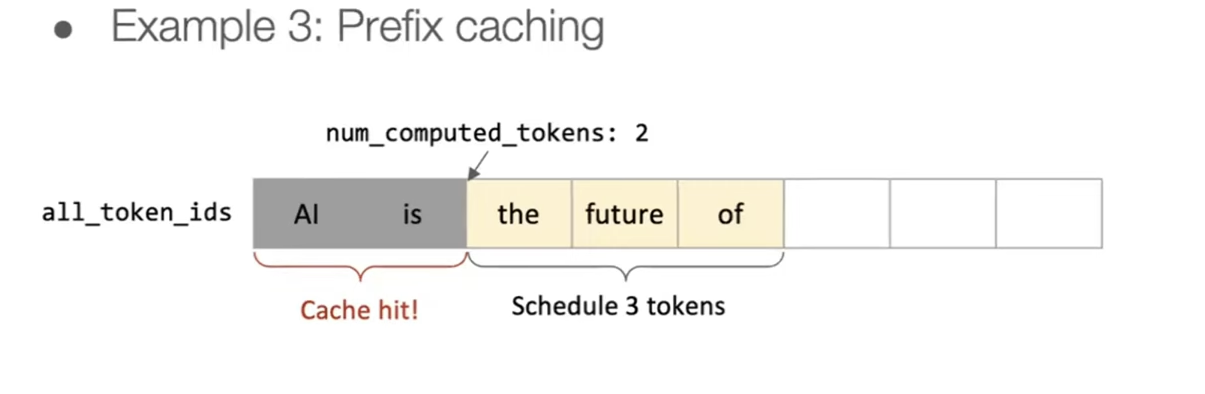

Modern vLLM tracks num_computed_tokens per request and explicitly decides how many new tokens to schedule in the next iteration. This makes it easier to mix prefill and decode fairly while keeping the GPU saturated.

Token budgeting in practice

When the scheduler runs, it picks a target number of tokens to compute for this step. That token budget gets split across:

- decode tokens for active requests

- prefill chunks for new requests

Each request tracks how many tokens have already been computed (num_computed_tokens) and how many it wants next. That small bookkeeping change makes the whole system smoother under load.

Putting it together

The end-to-end flow looks like this:

- Tokenize the prompt and create a request group.

- Prefill the prompt in chunks to build the initial KV cache.

- Decode tokens step-by-step, allocating new KV blocks as needed.

- Stream tokens back while the scheduler keeps batching new work.

I recently got a printed version of Modal's GPU Glossary which made me want to go even deeper and understand how vLLM works at a lower level on the GPU itself. Expect more posts in this series!